Editorial Note: Contemporary Hole

1 – When in 1977 the rapidly procured collection of modern Western art was unveiled to the public to inaugurate the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, wasn't its eventual retreat into the museum's cellar already anticipated– what became a fact after the 1979 Islamic revolution?

2 – The next time a work from the collection was taken out of museum storage was July 28, 1994 only to be traded with a16th century Persian manuscript at the Vienna International Airport. The work from the collection was Willem de Kooning's Woman III from 1952-53, and the manuscript (owned by an American collector) an incomplete copy of Abu'l Qasim Firdausi's Book of Kings known as the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp, richly illustrated with miniature paintings. It is usual that museums trade and replace works to enrich or fill in the gaps in their collection. But In this case the acquired manuscript is a total misplacement in a museum of contemporary art, let alone adjacent to the collection's modern Western art. But are objects really ever misplaced? Aren't proper dispositions always the misplaced ones?

3 – The extensive Western collection of the museum (the biggest outside the West with works from Braque, Léger, Duchamp, Pollock to Warhol, Smithson, Oppenheim etc.) was initially put together to 'mark' a sense of the 'contemporary' in ‘70s Iran, what in one respect was a self-eclipsing mark, disavowing its proximity to the erupting events outside the museum walls and always pointing to an 'elsewhere'. But soon this trait of the contemporary was redrawn with the collection's final withdrawal, with its incision this time swelling up a hole large enough to not only devour the collection but to embody – as such – the contemporaneity of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. In other words, the museum became truly 'contemporary' only with the withdrawal of the collection into the cellar, thus re-establishing a conjunction with modernity by means of an (art-)historical rift. After twenty years of being withheld from public, the collection began again to be – though very rarely – exhibited. But it retained an innate non-presence, such that a Warhol painting on view for instance would be a rehang of absence.

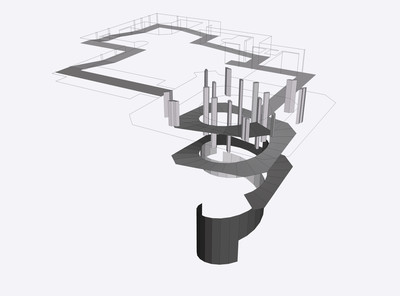

4 – The museum in central Tehran begins with a single floor above ground, and from there descends to lowered galleries inter-connected with ramps. The last room is the museum's storage, emphasized in its subsidence with a single spiral sloping down several levels bellow ground. It is as if upon entering the museum, one can simply curl down to the storage, bypassing the exhibition floors altogether.

5 – Clearly the insertion of the sixteenth century manuscript (as a retrieved lost heritage) into the 'archive' of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art was an attempt to restore the (art-)historical gap instituted with the acquisition of the modern Western collection. But the manuscript remains a mistaken recovery, or a cloaked exhumation via a temporal and geographical detour, for it will always carry a stranger's ghost within itself, namely that of the Western collection.

6 – The collection was acquired during the 1970's energy crisis, when Iran had an increased surplus revenue from crude oil. It was no coincidence that the National Iranian Oil Company would become the main financier of the purchase. While the developments between the first industrial extraction of crude oil in early twentieth century and the inauguration of the modern Western collection follow the culminating trace of modernity in Iran, there seems to have always been another groove running deeper underneath, widening occasionally bellow the surface.