- On November 22, 1963, the assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy was a clear sign of the death of modernism and extreme rationalism, evidence of emergence of postmodernism. The event, at that particular date, rendered many of rational modernist thinkers and theoreticians’ calculations irrelevant and symbolically put an end to a particular type of optimism and simplism in the public consciousness of the world.

The United States’ good-looking, well-dressed young president, with his idealistic and promising slogans – at least for the Americans – was no longer there, or at least, not on the earth! President Kennedy was now in heaven, regretfully looking down at an earth on which thereafter, since the moment the first bullet hit him, 2 x 2 was no longer 4. There were no longer any boundaries to anything.

- On May 3, 2003, I attended the 48th Oberhausen Film Festival to present my film … and I was born to sweet delight! … In a marginal section of the festival named “Catastrophe: Death on the Screen,” I watched a 24-minute movie by T. R. Utcho and Ant Farm titled The Eternal Frame, which profoundly affected my unconscious.

In their movie, an American product of 1975, twelve years after Kennedy’s assassination, the filmmakers intended to somehow recreate that significant historical event – at least from the Americans’ viewpoint, I stress again – and to give the film a realistic look by combining it with existing archival documentaries. The most outstanding point in the film was that the very attempts of Utcho and Ant Farm were entirely shown to the viewers as documentary proof of their attempts. This unique, strange and at the same time horrible parody, which was suitably selected and screened in the festival’s program strangely named “Death on the Screen,” not only showed the historical and ambiguous death of one of the effective figures in the world history, but also cried out from behind its narrative of another death: the death of boundaries.

Distinguishing the boundaries between reality and imagination, truth and falsehood, documentary picture and recreated picture, and, essentially, the boundary between the world of pictures and the surrounding world, as well as the extent of faithfulness of the picture to the existing reality is no longer possible, or even if possible, would not be as significant as it was before.

- February 11, 1979, the victory day of Iran’s Islamic revolution, was, this time, hoped by our parents to be a shift toward the new world. To that date, they had not been able to keep up with the world towards postmodernism. Because of the despotic regime in Iran, before the revolution, they had not had the chance to dismiss modernism and its manifestations, nor to look forward to postmodernism, the sound of which had reached them faintly from far away, from overseas, through Jimmy Hendrix’s guitar melody, Jim Morison’s anti-war lyrics and heavenly voice, Concept Rock and Pink Floyd.

- On September 22, 1980, a year since Pink Floyd had released their uproarious album The Wall in which they sang of destruction of the walls and boundaries, the soldiers of the Iraqi Ba’athist regime invaded the Iranian borders. As if they too wanted to remove the boundaries. But at what cost?

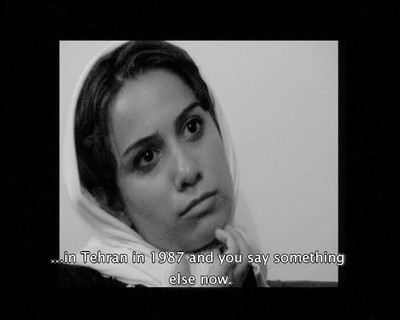

The Iranian people’s expectation of achieving an idealistic society and keeping up with what was going on in the world again became a distant fancy for them. There were soldiers who were killed one after another and missiles and bombs were falling down on innocent people. Now everybody was hopefully thinking of peace, not even of victory. At each sound of explosion, children who would be youngsters in the coming years thought whether they would ever reach youth or whether everything would end at that very moment. At those times, everything suggested that postmodernism had arrived, but quite intangibly. Some years later, the same young people who had heard and grown up with the explosions transformed into quite strange beings.

- And then came the time of satellites. They were coming one after another to show the wonders of the postmodern world to the people of this end of the globe, to those children who were now teenagers, who had grown up with the sound of explosions and war, who were now, seventeen years after the war, accustomed to a dual life, having learnt from their parents how to lie. The fetus of a kind of malignant, misshapen and creeping postmodernism was forming in the uterus of their minds, in the uterus of the mind of Iran’s future society.

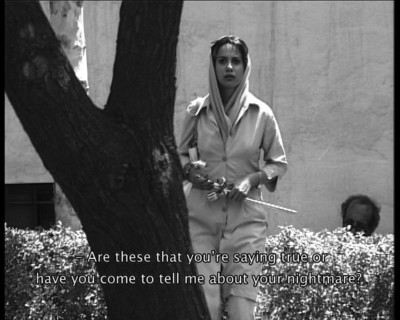

- After the victory of the 1979 revolution, a kind of traditional and unidirectional thinking, which had not vanished but was devaluated before the revolution, dominated the Iranian society. The pre-revolutionary generation, our parents who had experienced the pre-revolutionary lifestyle, now had to adapt themselves to a new way of life. For the women of the pre-revolutionary generation who were not used to any hijab, chador or scarf, it was a bit difficult to use such things to cover their heads and faces. In the first few years after the revolution there were protests by different women’s societies against that negation of freedom, but none of them were successful. (Ironically, several decades ago Shah Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran’s father had forbidden the hijab and government officials were assigned to pull down women’s hijabs or chadors in public!)

However, the parents, not knowing how to adapt to their new way of life, were suffering a kind of duality. They had wanted a traditional society but now they could not come to terms with it; it confused them. The duality and confusion between the two poles brought about a new generation with an odd lifestyle. Parents transmitted their duality to their children. They constantly warned their children not to mention what they saw at home or remembered from their pre-revolutionary lifestyle in schools or public places. On the other hand, those children were facing another way of life in schools and as reflected in the mass media that was very traditional and totally different from their own at home. Iranian postmodernism was forming.

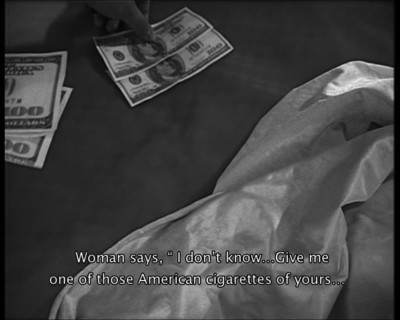

- VCRs that were once considered forbidden and against the conventions and norms of the Iranian society, were already legalized when satellite receivers and dishes arrived in Iran in 1990s. Everything changed. There was literally no house in Tehran without a dish on its roof. Now access to information and familiarity with wonders of the postmodern world was much easier than before. In the 1980s there was actually no communication with the outside world. There were only VCRs, which could be found in every house, despite being forbidden, as well as radio broadcasts that were usually jammed, and black market videocassettes which were – and still are! – traded among people. But now satellite networks were swarming in. (It is worth mentioning that owning dishes and watching satellite broadcasts is considered illicit and against the conventions of the society here.) And a few years later there came the Internet. Now everything was prepared for the birth of the offspring of a deformed postmodernism, moreover, of the Iranian kind, with an abnormally large head and a very small body.

- Teenagers were eventually growing into young people. Now there were no more explosions and fear of death. Little by little there would come the turn of defiance. Now they had MTV and Madonna. The world of music videos had battered down the boundaries and conventions. Now everybody had hundreds of TV channels at home from each of which wonderful and fascinating images flowed into the teenage eyes making them able to struggle, like amphibious creatures, between the traditions and conventions of society and what could be described as a new life, the wonders of the postmodern world which did not recognize any boundaries or conventions, and thus was very attractive.

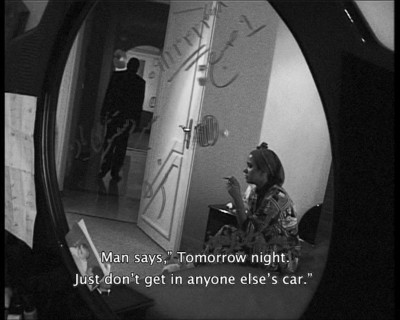

- We got used to lying easily and without worrying. Three to four years ago, the BBC, which is receivable here by courtesy of those dishes, televised a documentary report on one of the wonders of postmodern world. This time the wonder was we, the deformed newborn.

The BBC’s report showed a Tehran apartment in which a party was held. A bunch of young people, girls and boys, free from any conventions – and from any hijab, of course – were dancing to loud music and drinking something out of their glasses. Ironically, they all had entered the house in full hijab and would leave in the same way at the end of the party. People in the streets were also shown in full hijab. In the interviews, some of the young people at the party said to the reporter that they considered that way of life very exciting, some said they were accustomed to it.

Now, recalling the BBC’s documentary, I see that it reminds me of the parody of Kennedy’s assassination in The Eternal Frame. The movie was produced in 1975, the BBC’s report in 1999, i.e. the threshold of 2000. The movie was a recreation attempt, a parody, and the BBC report, a representation of a real life, which intrinsically is a constant recreation, without any attempt. Outside his/her home, everyone is his/her inside-the-home parody, and inside his/her home, his/her outside-the-home parody!

- On September 11, 2001, the attack on the Twin Towers formally announced the transition from postmodernism to a new era that could perhaps be called post postmodernism. 9/11 and the subsequent events, the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, which shocked not only the US but also the rest of the world, has now brought about a one-hundred-fold distrust. If, before 9/11, there was the slightest boundary between reality and imagination, truth and falsehood, lawfulness and lawlessness, it was totally destroyed afterwards. Did 9/11 or the subsequent wars really happen? Were a number of people really killed? Perhaps now Jean Baudrillard’s remark can resolutely be believed. In an interview with Libération on March 29, 1999, he remarked that the Gulf War had never happened.

Considering the Persian Gulf War a postmodern phenomenon, Baudrillard believed that everything was a video game on the world’s TV screen. Could we, in the same way, say that 9/11 has never happened, or that the US has never attacked Afghanistan and Iraq? Isn’t all that a TV show or commercial or, as Baudrillard puts it, a TV game? And finally, can those greenish night-vision images of the Iraq war showing US soldiers in assault mode be called realities of war? Nobody would answer these questions because everything has become more complicated in the postmodern world. Now, not only we (Iranians), but the whole world is habituated to lying.

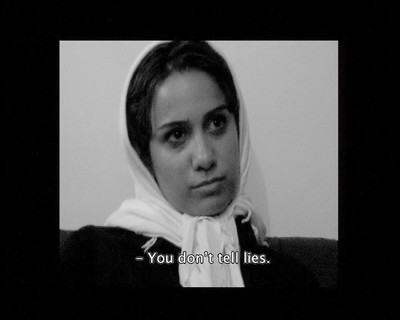

- On November 16, 1977, one year and a few months before the Iranian revolution, I was born. 23 years later, on November 16, 2002, my film, … and I was born to sweet delight … was ready for screening. About a year later, in September 2002, on the first anniversary of 9/11, I made I am a purifier, a movie full of easily made lies: A prostitute who receives her customers while fully dressed and scarfed and goes to bed with them in the same way. This is a kind of lie we are accustomed to. And I am one of those children I described before. My name is Kiarash Anvary. I was born two years after The Eternal Frame was made.