Pages: The archive is usually the site of the past. It holds documents that have somehow survived over time and now have come to represent traces for a collective memory of a nation, a people or a social group. But more than that, the archives of our time have become sites of re-archiving and of reproducing documents. For example, electronic archives such as Youtube or Facebook, where a single document is posted and reposted time and again through a process of cut-and-paste. If archives are incomplete, it is no longer because of the documents that did not survive the passing of time, but of what is still to be inserted or re-invented into them. The archive can be understood as the open-ended site for the production of anticipated memories and connectivities. In his article 'Archive Aspiration', which takes the example of the diasporic archive, Appadurai writes that the migrant archive is the main site of negotiation between collective memory and desire.1 This characteristic of the archive (which according to Appadurai is the intensified form of all archives) is precisely what official institutional or ideologically driven archives tend to suppress. In our time there seems to be an increased desire to produce undecidable 'documents' that form the endlessly open and flexible archive. Clearly this change in the experience of the archive requires a revision of historiography and cultural research. In your view, what are the implications of this?

Norman Klein: Traditionally, as an instrument of power, the archive has been defined as an official collection of documents, where surveillance and control are its dominant function. Appadurai shifts that definition into something that is less stable, and can be migratory. Archive then is mediated, as in the tracking of immigrants or migrants within a globalized economy. That would suggest a more invaded archive, where social memory and material culture intersect somehow (in ways as yet to be discovered, perhaps a field of research that needs archiving, let us say). In my work on archive, that direction is not entirely helpful. It presumes a distinction that almost dissolves for me, for example: whether a place where documents are official (a legal record) or an attic where family remnants have been assembled for a private purpose. The archive is a fictional act, a making of story out of a pile of traces.2

1. More to the point, I like to see ‘archive as a verb’. It is the "act of assemblage," as Margo Bistis writes (for the soon to be published Imaginary Twentieth Century).3 We start then with very different examples, and wind up in the archiving of the migratory.

2. Let us open to the first page of a novel, or view the first five minutes of a feature film. There may be a back-story. In fact (as fiction) back-story is essential to the ambiance of reading. It is the unspoken that came before. The diegesis, or filigree of events before, must be implied, as if the story were racing against time and dissolving memory. In tragedies set in a post war situations, like the women of Troy (Euripides), the characters reenact the unspoken, the lost decade when war stole their lives. But they must reenact the unspoken within a single day. They are essentially archiving dramatically. They are forced to condense meaning, one might say, only enough memory to keep the ghost of their dead husbands alive, but not too much to bear. They must archive selectively.

3. Official records are much the same, in many respects. Mediation is even more obviously an archiving. We are given a construction, but allowed to also see the bones of the house. As one researches through a collection, a database, there is always a haunted ideology, of course. What is left out tells us more than what is included. No matter how complete the archive may seem, it is partial. It may seem thorough, but that may be in order to hide something more important. Rarely does a researcher find the heart of the matter in a collection. More likely, the heart has been consumed or partially removed. Otherwise, the collection would not have survived. It is like a plate of food after it has been eaten. We study the plate for signs of what was eaten.

4. Unquestionably, the impact of the Internet has accelerated archiving to the point of madness, in many cases. ‘The fat finger’ can generate a stock market crash. Records can be deleted in a thousandth of a second. Filters of all kinds can reassemble data into a thousand shapes. Archiving has almost become sculptural.

5. In a larger sense, as archiving turns increasingly into a migratory blogospheric process, we are living inside the ‘end of the political Enlightenment’, at least in the West – the end of the tradition of common law and rule-of-law as an equalizer, as a shared code. There are many reasons for this ending. One that occurs to me as I type away late at night is the following: Archiving takes place in a fraction of a second, too fast for anyone to study. Then, a day later, the truth is old news, too old to be studied. We live in an autistic knowledge culture, incredibly migratory. At the same time, the migrations of real people due to globalism are just as easily forgotten – on the spot, in a second. It was always easy to be ignored when you are marginal; but now, through fictive archiving, media culture pretends to notice. We think we are actually keeping track, but archiving is more often an act of erasure and forgetting. It is hard work to archive second by second.

6. Archiving is a scripted space: it seems to privilege the person navigating through it. But in fact, the design is predetermined. Thus, the oligarchs and owners of the program usually win.

We try to find a balanced view: This new migratory form of archiving does offer the viewer a chance to intervene in the official record, to comment on real facts as social media. Of course, much of that is just a way of barking at the moon. Where does political illusion meet political action, where does migratory knowledge liberate us today? And yet, particularly now, as group hysteria, the migratory (collective) act of archiving has actually dissolved the official record. It overwhelmed official facts with shared hysterical facts. In the US, archiving turned into mob action, into collective schizophrenia; into ten thousand unofficial lies and racist innuendoes, guided by wealthy right-wing investors.

Archiving today – as a verb – easily covers up the official record. It promises to replace the rule of law by folkloric intervention. It promises to “tea-party” it, to have non-lawyers remake the law. That sounds liberating... Perhaps some day, this will be a liberationist act. Right now, it merely glorifies capitalist risk. It is another artificial theology about market domination. It hopes that deregulation will increase imperialism, even at home. In some ways, it will, of course, but not as imperialism once was. Now, erasure by way of archiving makes all forms of imperialism easy to camouflage, even when you are begging to become a serf, asking to be colonized. In other words, the Tea-party movement wants to accelerate their own feudalistic future – and ours along with it, all to save the white male (from what is not always entirely clear). Thus, archiving, as a collective wiki style of memory, has become a vigilante act in our time. It turned social memory into a blizzard of factoids that poisoned what remained of our national politics.

A confession: I must admit, however, that poisoning the system is charming (I remember trying my best during my youth). It is so pleasant, that the true facts of the matter are hardly relevant. Who really cares? It is more fun to intervene, to archive on your own. You feel for the moment as if you are transforming hegemony, not reinforcing it. Archiving becomes a theatrical copy of revolution. It becomes solidarity on behalf of your own self-immolation. You can actually dissolve a government this way, without offering the slightest alternative. Migratory archiving travels too fast to make actual policy, only to dismantle infrastructure. It is a kind of grand peur, like the summer of 1789 in France, but without anything else; so the global investors win everything.

Thus, obviously, while complaining about immigration, Americans should look at their own self-migratory insanity. Immigrants are in no way responsible for the insidious way that Americans are dismantling themselves, hiring themselves out as serfs. That is so evident, the joke is literally on us.

7. Here I would like to shift my discussion to archive as storytelling, with a tradition going back centuries, even millennia. I often compare archive – as a verb – to the picaresque novel (characteristic of seventeenth and eighteenth century fiction). Picaresque is episodic, filled with the bones of lost places, what I call a wunderroman, a fictional archive that operates a bit like a curiosity cabinet. The character journeys into a manic stillness. You adapt to a world that refuses to change, but is never at rest. The world will simply not evolve; it is frozen somehow, but filled with conmen and swindlers. The picaresque is a road story about the picaro (or man of the road), who wound up on another path, every bit as diabolical as the first. Archiving then turns into tragicomedy, rather like Marx's description of the Revolution of 1848 in France.4 Outwardly, the revolution seems a liberation of the lower classes, the layers of proletariat (and certainly proletarian revolution is what Marx had promised in the Communist Manifesto, only months before). But Marx as journalist was forced to notice that the revolution provided the same capitalist forces a new way to tighten their grip, to look more ‘modern’, but just as relentless.

8. If we stay on the literary aspects of archiving, many other directions emerge. Here are a few: Migratory implies a more reader-oriented telling, a less formal, more unedited structure – at least in our off-the-cuff, Internet civilization. However, underneath the instant genius and bushwah on our monitor, underneath all this hyperlinking, real Trojan women are still waiting, surviving, adapting, in migratory nightmares around the world.

9. The problem can be summarized simply enough: Archive has grown extremely relevant in our time. Databases have matured into new instruments of power. But the search engines that turn data into archive are endlessly transitioning (always in migration, unlike old-fashioned ‘archives’). They are risky; they often pose as liberation, but are often more like mob rule governed by wealth and risk capitalism.

And yet, the liberating possibilities of archiving should not be ignored. The archival act is often a collective action – as a new form of social memory. Perverse as it may be, this magnetic impulse must somehow be harnessed better. To coin a phrase from American history, we must assume a frontier vigilance about knowledge and manipulation when we study archiving.

As I roll toward the conclusion, I'll return briefly to the immigrant (as the son of immigrants who has spent most of his life in immigrant neighborhoods in the U.S.). All residents in the US – citizens and immigrants alike – are becoming foreigners in their own economy. That is why citizens here feel increasingly like immigrants, particularly since the Crash.

10. Thus the shift of archive to a verb reminds us that a new hazardous civilization is emerging. Capital is migrating even faster. The nation state is being restructured even faster. The official record migrates into vapor, as social media. Rupert-Murdoch style news turns into proxy government, pretending to keep honest records. In terms of knowledge, we in the US are forced to be hunters and gatherers, inside a drought. This is the story – the archiving – that I have decided to track. I believe that it will eventually lead to the remaking of the American political system altogether. But that will take a long time, decades.

I hear dogs barking outside at nothing at all, just keeping each other company. I hear people leaving the evangelical church down the block. Cars roaring up and down the hillsides mix with a helicopter far away. I collect the moment, find the noise relaxing.

* * *

Pages: You refer to archive an empty plate of food that we study for signs of what was eaten, gatherers inside a drought. Yet you see the possibility of tracking new narratives of the moment, of redeeming the erased to allow new social memories? Can you give examples of your own work with archives?

Norman Klein: I will conclude by offering an alternative form to archive. To present this alternative, I will first clarify what I am not doing (1), then give a summary of an ongoing project (2).

1. Current theories about the archive often evolve from their earlier ‘public meaning’. That is: the archive was a ‘public record’ that officials used to enforce policies to. In nineteenth century Europe, the state (national and regional) made an enormous fuss about its archives becoming more available. They were presumably a point where power and ‘objectivity’ met as good government, as freedom of information. Archives became shrines to the illusion (and occasionally the fact) of democracy.

To go back even further, we know that Baroque Europe (in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries) was already obsessed with official archives as tools for the purification of the Catholic Church (the Counter Reformation) and as signals of a shift in how power operated. For example, the census was a tool that bourgeois royal tax farmers (as they were called) used in France. Tax farmers paid money to the king to replace the regional power of nobility to collect taxes. With their census records, tax farmers could even get bank loans, based on how much they would skim from the revenues.

So the official archives after the Revolution (for all to see) were presumably a step toward the rights of man. But there remains the fundamental role of archive:

1a. No matter how open or repressed, the official archive was the last word, like a verdict in court. There was no way to correct the verdict, whether a census, or a tax record, or a marriage. It was a secular cognate of the divine word: its matter-of-fact was equivalent to the word of God.

2b. As a related example, particularly for the period after 1850 in Europe, there was a cognate to the archive that should be mentioned here: the atlas.

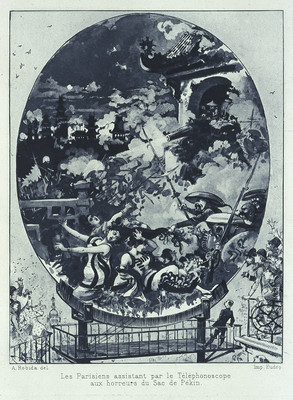

The atlas was a pictural (or even picturesque) archive that served as a visual mapping of place (a city, a country, an ethnicity). After 1850, these became enormously popular, in hundreds of editions, almost like books of hours had been in the fifteenth century. The visual atlas was a form of armchair tourism, infinite in detail, and heavily populated with human facts (what an exotic people did for a living, their customs, their topography, their psyche, etcetera). The most famous ‘private’ visual atlas was probably the Kahn archive of the world, 1908-31, sponsored by the Parisian banker Albert Kahn; a ‘map’ of the world that contained thousands of photographs and films, mostly as long shots and pans— processional more than dramatic imagery.5

That suggests a definition of atlas within my argument for this essay: Like an official archive, the atlas is also presumably ‘complete’. It is presented as thorough, like a map where no place can be ignored. It was a science of the actual, particular to the era dominated by European colonialism.

2. Now we shift. Obviously the official archive and the atlas are both fictions in how they are programmed. There is no need to argue that. But what if we emphasize the archive as fictional, as Balzac did in his ‘Human Comedy’ (twenty novels as a master atlas of French life 1815-30; a history of mores, he called it).

Where does that kind of human comedy take us today – with the Internet as our archive; browsing as the archive-as-verb; computer graphics as precision-tooled fictions that can archive anything?

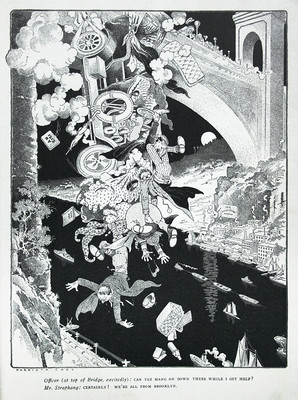

This month, after six years of work, I am completing a gigantic archival project. Along with the curator (and co-director) Margo Bistis, I have invented a novel that includes an archive of 2,200 images. Broadly speaking, it is a story about how the twentieth century was imagined before it happened.6

But the major instruments of this archive are a 60,000 word novel (to be published as a book), and a massive interface that intermingles with the book, and will be available through a password on line. The interface requires 40,000 gigabytes, includes interpretive maps (one for each of the twelve chapters), its own music/sound archival score, its own voiceovers. It is thus a tripartite archive, an engine with three gears: novel in print; interface on line; historical web site.

The purpose of this archive is to remain thoroughly incomplete, like collective memory itself. The more factual it gets, the more fictional it becomes. The story does make sense, from plot point to plot point: it delivers ‘endless’ facts in very coherent streams, easy to track. However, the facts inside these streams are about events that cannot be proven; though they probably happened. I say probably if you want to believe the novel; and certainly the archive is utterly ‘true’, in its way. It does contain real documents, from real magazines, collections, even official archives for some of it, like the Library of Congress (in Washington, D.C.), or special collections from major libraries.

Let me thread the needle for a moment: After all, a story that is a ‘lie’ must be based on some version of the truth, or else it is just a lie. That is closer to, let us say, speculative science fiction. There, the author often promises non-truth, and delivers thoroughly; to the reader’s delight— that’s a fact. The Imaginary Twentieth Century is not speculative in that way.

If I tell you, the reader, that everything I write for the next two pages will be a complete lie, that would also be a fact. But The Imaginary Twentieth Century1 must overlap fact/fiction much more. It must be an unstable lie, an incomplete that someone – a character in the story – planned that way.

A summary statement is needed here, before I fall into a Zeno’s Paradox: In The Imaginary Twentieth Century, many of the historical events did occur, though an atlas of these events turns out to be a kind of wallpaper, to hide cracks in the plaster behind it.

Part of the reason is its principal ‘theme’, a trope that returns often — about the collective act of misremembering. There were hundreds of thousands of pictures about the twentieth century before it took place. But no more than five per cent of these imaginings were truly acted out. Put another way: the future is always a caricature of the present. It is the present as a future of the past. Otherwise, who can plan at all?

However, as soon as the ‘real’ future— real events — intrude, these earlier conjectures, even from months before, suddenly look quaint. However, the imaginary futures do not disappear; they leave a residue of actions not taken. This residue finds its way into science fiction and techno curiosities — on film, in devices at world’s fairs, in Shanghai, or in Epcot at Disney World.

To recap: Archive is often collective memory. It is material culture; which is quite different from a divine instrument of the state. Collective memory is about displacement, erasure, evasion and distortion. To some degree, in archives, fact and fiction coexist strangely, in what historians used to call the collective psyche.

The archive still needs a story, a construction of course. In The Imaginary Twentieth Century, the story centers on a woman and her four confused suitors — and her uncle, a political insider. The story has a time frame, 1893-1925. But its narrative pleasure lies in its incompleteness. The archive that it presents is a gigantic record of political hoaxes, and the engineering of half-truths. The pleasure of navigating these lies not simply in the places one locates, in plot points one finds— but in the ‘futures’ hidden there: the blank spaces in between; clues that were edited out.

The imagery itself (2,200 scans) are almost purely about the missing. If they were a piano, they would be the black keys. Imagine an archive, then, in a stream where misunderstanding is just as believable as fact. As the uncle often explains, fiction is much more believable than ‘the truth of the matter’.

Imagine an archive that belongs clearly to our commodified, half-baked world today, where real violence is often imaginary, as perverse as that sounds — where the fact and fiction coexist like crosswinds; but have real consequences. Real simulated money disappears, real lives are lost. We live very much in an archive based on misremembering.

The archive is more than ever a construction: breaths between. It is now supposed to be the instrument of power that we all share in social networks. But it is very often the same misery, much as it always was. Now archiving is presumably an open source; but the more open it is, the more forgetful and fictional it becomes, just like those official records centuries ago. We are all tax farmers now, but only some of us ever collect.

We can broaden this a bit further: Archiving lies at the heart of all storytelling. The program that guides it is an author. It speaks to us through narrators. Sometimes we are a narrator. Increasingly, due to the Internet, there are many narrators at once; and often highly unreliable authors, who can shape the data, add non-facts easily, decide which events should be remembered.

So the final question remains for the reader to interpret: Will this fictional/factual mode of archiving offer the democratic action that open source used to suggest? Or is it merely another way for public instruments of power to operate? Today, I am reading about the assassination attempt on a U.S. congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, in Tucson Arizona. Much of the evidence is on line, left by the assassin.

His rambling are as mad as anything one could imagine. This is a fiction I would have trouble even inventing; and I can lie fairly comfortably. The spaces between, the breathing apparatus of the archive, has always been a tool of assassins. We are none of us surprised. But the humanity behind it, the attempts to take charge of collective archiving, will dominate our civilization for decades.

Culturally, the future of how archive incubates will be a primary job for writers, artists and critics; and librarians, scholars, media designers. It is like the reinvention of the novel itself; and perhaps even political democracy itself. One likes to hope.

Footnotes

1- Archive and Aspiration, Arjun Appadurai, Information is Alive: Art and Theory on Archiving and Retriving Data, Joke Brouwer, Arjen Mulder, Susan Charlton, V2-NAi Publishers, 2003

2- Appadurai’s essay is linked to theories of the 1990’s, where archiving was closely linked to computer databases. For example, my first media novel—very much about fiction/fact and archive-- was called a “database novel” by the publisher; and I essentially agreed back then (Bleeding Through, 2003). But I learned so much about archiving from all my projects, I now feel quite differently.While the nineties impulse to expand on “data-sampling” continues (in conferences and papers on the Digital Humanities, and research on science-and-media mapping)-- along with continued philosophical responses to Benjamin, Foucault, Derrida and others-- I am convinced that the literary possibilities of archiving still remain mostly undeveloped. I am increasingly asked to train artists and designers in this literary potential, through seminars at Cal Arts and at Art Center, for example. Through these seminars, I can see changes toward archiving-as-literature in only the past five years. Quite suddenly, it seems, as if passing a threshold, social media have changed how students see archives. The act of retrieval has become as intuitive as epistolary traditions were in 1700. In that sense, the way that we handle social media could evolve into a kind of novel in the sense that letters and diaries did circa 1900. As a digital culture, since 2000, we have moved from multi-tasking to clustering (that is, from ten directions at once, to ten functions toward the same task). As a result, the transitive and sculptural possibilities are spectacular. Many of my students have tried to build mechanisms that capture this topology, this architectonic engine that is archiving.As a final point in regard to the task of archiving (re Appadurai and others), there is one more field that needs to be mentioned: archiving as mnemonic architecture, in new work on memory theaters (far beyond earlier studies, like The Art of Memory by Frances Yates). That is: sculptural work on collective memory as environments (by artists like Deborah Aschheim, for example). This, of course, is also a response to the video mapping of memory itself by scientists involved in memory and the brain; the archiving of memories turns into set of trails and clusters that can be filmed and built.

3- For more information, and updates on The Imaginary 20th Century Project, see the web site

www.imaginary20thcentury.com

4- Karl Marx, the opening page of The Class Struggles in France, 1848 to 1850, in numerous editions.

5- The most recent study on Kahn’s archive: Paula Amad, Counter-Archive: Film, the Everyday, and Albert Kahn's Archives de la Planète, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010). This monograph is part of yet another field in archiving that refers back to Aby Warburg’s work in the 1920’s-- to art history and photo collections as scripted environments (also related to the history of art installations since the early sixties, and various installation artists who specialize in archival method, like Peter Friedl). There is also the ongoing crisis in archiving brought about by lapsed platforms, where video art disappears when a new device or software erases an older system. This has generated all sorts of ironies in artwork, because our collective memory through media often vanishes, as if it were set on fire by Apple or Microsoft or Adobe, as if the computer business were like the fire that destroyed the ancient library of Alexandria.